This blog post is another one of those that I should have written a while ago as the topic of story point based estimation keeps coming up again and again. To really understand why story point based estimation is important for Agile delivery, I think I need to explain the idea behind it.

The purpose of estimates is to get a good idea of how much work needs to be done to achieve a certain outcome. To do that, the estimate should be accurate and reasonably precise. This is where the crux of the problem is: precision. If I’d asked you how long it takes to fly from Sydney to Los Angeles, you would not respond with an estimate that includes minutes and seconds because you know that it is ineffective as it is not precise. The more precise we get in estimates, the more we pretend to be able to do something that we cannot do: work at that level of precision. The other downside of precision is that each level of precision requires more work to be put in the estimation process. I have done many IT projects and can tell you that my estimates for each individual task is off by as much as +/- 100% easily, but in aggregate my estimates are pretty good.

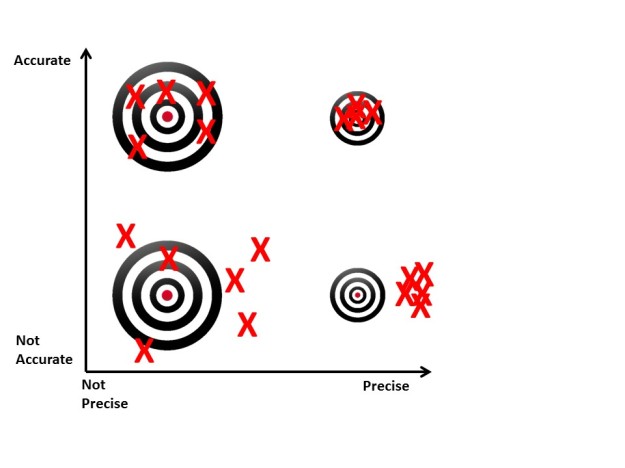

Let’s explore the difference between accuracy and precision a bit further:

It should be clear that we care more about accuracy than we care about precision and that is exactly what story points do for me. I am spending just the necessary amount of time estimating to be reasonably accurate without trying to become too precise. The usual Fibonacci sequence (1,2,3,5,8,…) helps to avoid false precision as well. Now, to be honest we could call it 1,2,3,5,8 days and be done with it as that would probably achieve the same outcome as story points. The problem is that for some reason we are a lot more tempted to use the other in between numbers when we talk about days. We are also tempted to equate days of effort with schedule, and most of us can attest that a day of effort is hardly ever done in a day of schedule as we get distracted, multi-task or attend meetings. The story point concept provides us with a nice abstraction that prevents these mental shortcuts and keeps us focused on the relative nature of the estimate.

The other thing that should be obvious is that a day of effort for one person is not the same as a day of effort for another person. More experienced people need less time than more junior people, so any estimate in hours or days is flawed unless you know who will do it. Story points do not suffer from this problem as they are relative to other stories and independent to the person performing the tasks associated with it.

The other nice thing with Agile estimation is that it usually is a lot closer to the often recommended Delphi technique, which asks multiple independent experts to estimate tasks and then aggregate it. Planning poker is a pretty close approximation of the Delphi technique and is therefore much more accurate than estimates done by individuals.

But why do we need a point system at all, why do we not just do relative sizing in t-shirt sizes or something similar. As I have explored in another blogpost (link), teams need a goal line whenever there is a certain outcome to be achieved. The easiest way to do so is by tracking progress on a numerical scale (see Agile reporting post). And if you work in a larger organisation you probably want to have some common currency to be able to measure the throughput (see productivity blog) and be able to swap stories between teams. Here I will go with the guidance that SAFe provides, start with a point being roughly a full day of work and estimate everything else relative to that. On a regular basis bring members of the team together to estimate an example set of stories and use this process to recalibrate the relative understanding of size.

So what if things change? One thing that people are always concerned about is scope creep or inaccurate estimates. For a story by itself I don’t have strong opinions on whether or not you update the size once you realise there is more or less work than expected. However, if you use larger buckets for your initial estimates (e.g. a feature that should roughly take you 100 pts), then I think it is important to measure how many points the stories of that feature actually add up to – if that is different to 100 pts in this case you have some real scope change that will impact your timelines.

To close off, I will provide a few helpful links to other comments/blogs about story points which you can use to learn more about this topic:

http://www.scruminc.com/story-points-why-are-they-better-than/

http://collaboration.csc.ncsu.edu/laurie/Papers/ESEM11_SCRUM_Experience_CameraReady.pdf

https://www.scrum.org/Forums/aft/564

http://www.mlcarey321.com/2013/08/normalized-story-points.html